Nah, even Napoleon could learn his lesson, especially ITTL where he barely won a victory by the skin of his teeth, he knows to not rock the European boat outside of soft diplomacy, so he will be looking out towards the rest of the world to exercise influence and rebuilding the navy to bring French power towards the rest of the globe.honestly i don't think so Napoleon has proven france can achieve anyhting by force. The idea france somehow lost all european territorial expansion seems foolish if anything it showed they take almost all of europe. If any issue happens on the continent we'll invade you and know everyone knows its true. Rebuilding for france doesn't take along give them 5 years and they will be fine. Again coalition has to keep france checked If france foreign expansion is not checked its just going to translate to mainland france growing stronger, coalition it just sigining death warrants for later. After all why shouldn't france not have polish ally? Or dominate italy? Hell an argument can be made that france is the true leader of the germans now. They got the rhine austria sold them off and allowed those french aligned german states to exist, saxony, and south germans. French goals have simply changed from west of the rhine to east of the rhine now.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The New Order: A Successful Selim III

- Thread starter Vinization

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 19 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 12: One Final Effort Part 13: The Congress of Frankfurt Part 14: The Spectre of Revolution Part 15: Papers and Muskets Map: Europe after the Congress of Frankfurt Part 16: Carrots, Sticks and Daggers Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear Part 18: An Eagle Rebornrandom questions but can you share with us the status of the Parthenon sculptures, and Rosetta stone? did Britain still get the former and in the latter did the french return it along with other stuff they stole from Egypt?

He and his family have become like the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, I wonder if this will give them ideas when their borders are forcefully opened.Despite having won the war on paper, the Sublime Porte had little reason to celebrate: the mere fact the situation got so bad in the first place made it clear the Ottoman state still had serious flaws, despite the success of the New Order and its reforms. The only person who truly gained something from the whole mess was Muhammad Ali Pasha: with Hurshid out of the way, he no longer had any real challengers for the title of grand vizier, and he was free to work on ensuring Ibrahim succeeded him.

The irony of European Liberal thinker volunteering in the Imperial Russia Army, would just be hilarious to see play. Especially if they get thrown into Siberia in the aftermath.Liberals throughout Europe were shocked and outraged that their countries' governments did nothing to assist the Greek rebels. Said governments just stood and watched, even as the Ottoman military reduced Missolonghi to rubble, laid waste to many islands in the Aegean Sea (killing and enslaving thousands of people in the process (12)) and turned much of the Peloponnese into ash. They would, eventually, act on those feelings.

For now, all they could do was gather strength bide their time.

Or they just remain in ottoman empire?random questions but can you share with us the status of the Parthenon sculptures, and Rosetta stone? did Britain still get the former and in the latter did the french return it along with other stuff they stole from Egypt?

The irony of European Liberal thinker volunteering in the Imperial Russia Army, would just be hilarious to see play. Especially if they get thrown into Siberia in the aftermath.

You are underestimating them. They'll gain political power within their own countries and act .

On that subject Russia also had its own liberals, it's jut that just like Austria it was able to deal with them a lot better , so liberal threat will probably come from other parts of Europe.

It just tied into a fixation I had of Lord Byron getting disillusioned by the Greek rebellion earlier in the threat.You are underestimating them. They'll gain political power within their own countries and act .

On that subject Russia also had its own liberals, it's jut that just like Austria it was able to deal with them a lot better , so liberal threat will probably come from other parts of Europe.

Although I am curious if the equivalent to the 1848 revolutions will see a Hungarian invasion of the Balkans.

It just tied into a fixation I had of Lord Byron getting disillusioned by the Greek rebellion earlier in the threat.

Although I am curious if the equivalent to the 1848 revolutions will see a Hungarian invasion of the Balkans.

Well Hungarian revolution will be interesting without Russian intervention. But honestly i still expect Austria to suppress them , maybe they are forced to come to terms with Hungarians earlier and form A-U. But they'll keep them as part of the Empire non the less.

Regarding potential invasion of the Balkans? They can try but honestly population will chase them off with pitchforks. Ottoman rule of the Balkans was mostly peaceful until Empire hit economic difficulties, but with things going up its set to remain peaceful. Bosnia for its part is well integrated and has quite sizable Muslim population.

Serbs on their part actually have more autonomy under the Ottomans as of right now than they had in Hungarian portions of the Empire and Austria-Hungary itself only had problem with independent Slavic state forming and threatening them. Without independence movements in the Balkans Austria will probably remain focused on Italy and Germany.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is with great pleasure that I announce that I am working on this TL once again! What's more, the next few chapters will deal with a corner of the world I haven't touched so far: the Americas. The first country to be addressed is one whose name was already mentioned in one of the last updates.

Interested in seeing how the Americas have changed thanks to an earlier Anglo-American War and Napoleonic wars. Definitely gonna put Spain in a better position to stamp out the revolutionaries.Ladies and gentlemen, it is with great pleasure that I announce that I am working on this TL once again! What's more, the next few chapters will deal with a corner of the world I haven't touched so far: the Americas. The first country to be addressed is one whose name was already mentioned in one of the last updates.

Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear

------------------

Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear

If there was one place in the Americas where the opulence and horror which dominated the colonial era were at their most visible, it would likely be the French colony of Saint-Domingue, located on the western third of the island of Hispaniola. While most societies in the continent were marked by a rigid caste system in which skin color was almost as important as material wealth, nowhere was this division more extreme than in Saint-Domingue: at the top of the social pyramid sat the grands blancs ("great whites"), who, as their name suggested, were an exceedingly small minority of white planters who owned most of the land in the colony and, as a result, held enormous political influence. Below them were the gens de couleur libres (free people of color), many of whom were also wealthy plantation owners (who were, nevertheless, denied several rights and privileges due to their mixed ancestry), and the petits blancs ("little whites"), who served in a variety of jobs, from shopkeepers to small farmers and administrative officials.

Below these groups, all with their own agendas and internecine rivalries, were the people whose blood greased the wheels of Saint-Domingue's economy: hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of enslaved people, who outnumbered everyone else by a margin of ten to one. It was they who, working from sunrise until sunset, ensured the colony's prosperity by cultivating and harvesting the coffee, indigo and sugar which made it France's crown jewel. It was a job they performed under the worst, most horrific conditions imaginable: deaths among the enslaved were so high, thanks to the sweltering heat and diseases, their owners preferred to work them to death and import new Africans rather than provide even the most basic amenities for them. The lucky ones escaped the plantations and formed maroon communities in the mountains, beyond the authorities' reach, while those who weren't faced a likely short life rife with physical and, in the case of women, sexual abuse.

This was a society full of tensions which had simmered for decades, and, naturally, news of the outbreak of the French Revolution threw it into flux, with each group doing its best to take advantage of the turmoil that engulfed the metropole. The grands blancs not only sought to maintain their privileges, but also wished an end to the myriad of economic restrictions that shackled Saint-Domingue's economy to France. The free people of color, in the meantime, desired equal rights regardless of race, something they had been agitating for for decades at this point, while the petits blancs, who saw them as economic rivals, wished to prevent that and allied with their fellow whites in order to do so.

Then, on October 1790, Vincent Ogé, a free person of color and wealthy planter, began a rebellion against the colonial government, which refused to enact a law extending full voting rights to people who belonged to his social class. His uprising was short-lived, however: gathering just 300 followers in the outskirts of the city of Cap-Français, he was forced to flee to the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, whose authorities handed him to the French. After a short trial, Ogé was sentenced to death and broken on the wheel on February 6 1791, a grisly demise which transformed him into a martyr. As open fighting broke out between the whites, free people of color and the French colonial government (beholden to the whims of an ever turbulent National Assembly back in Paris), the enslaved watched everything from the sidelines.

Then, on the night of August 21 1791, they finally made their move.

Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear

If there was one place in the Americas where the opulence and horror which dominated the colonial era were at their most visible, it would likely be the French colony of Saint-Domingue, located on the western third of the island of Hispaniola. While most societies in the continent were marked by a rigid caste system in which skin color was almost as important as material wealth, nowhere was this division more extreme than in Saint-Domingue: at the top of the social pyramid sat the grands blancs ("great whites"), who, as their name suggested, were an exceedingly small minority of white planters who owned most of the land in the colony and, as a result, held enormous political influence. Below them were the gens de couleur libres (free people of color), many of whom were also wealthy plantation owners (who were, nevertheless, denied several rights and privileges due to their mixed ancestry), and the petits blancs ("little whites"), who served in a variety of jobs, from shopkeepers to small farmers and administrative officials.

Below these groups, all with their own agendas and internecine rivalries, were the people whose blood greased the wheels of Saint-Domingue's economy: hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of enslaved people, who outnumbered everyone else by a margin of ten to one. It was they who, working from sunrise until sunset, ensured the colony's prosperity by cultivating and harvesting the coffee, indigo and sugar which made it France's crown jewel. It was a job they performed under the worst, most horrific conditions imaginable: deaths among the enslaved were so high, thanks to the sweltering heat and diseases, their owners preferred to work them to death and import new Africans rather than provide even the most basic amenities for them. The lucky ones escaped the plantations and formed maroon communities in the mountains, beyond the authorities' reach, while those who weren't faced a likely short life rife with physical and, in the case of women, sexual abuse.

This was a society full of tensions which had simmered for decades, and, naturally, news of the outbreak of the French Revolution threw it into flux, with each group doing its best to take advantage of the turmoil that engulfed the metropole. The grands blancs not only sought to maintain their privileges, but also wished an end to the myriad of economic restrictions that shackled Saint-Domingue's economy to France. The free people of color, in the meantime, desired equal rights regardless of race, something they had been agitating for for decades at this point, while the petits blancs, who saw them as economic rivals, wished to prevent that and allied with their fellow whites in order to do so.

Then, on October 1790, Vincent Ogé, a free person of color and wealthy planter, began a rebellion against the colonial government, which refused to enact a law extending full voting rights to people who belonged to his social class. His uprising was short-lived, however: gathering just 300 followers in the outskirts of the city of Cap-Français, he was forced to flee to the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, whose authorities handed him to the French. After a short trial, Ogé was sentenced to death and broken on the wheel on February 6 1791, a grisly demise which transformed him into a martyr. As open fighting broke out between the whites, free people of color and the French colonial government (beholden to the whims of an ever turbulent National Assembly back in Paris), the enslaved watched everything from the sidelines.

Then, on the night of August 21 1791, they finally made their move.

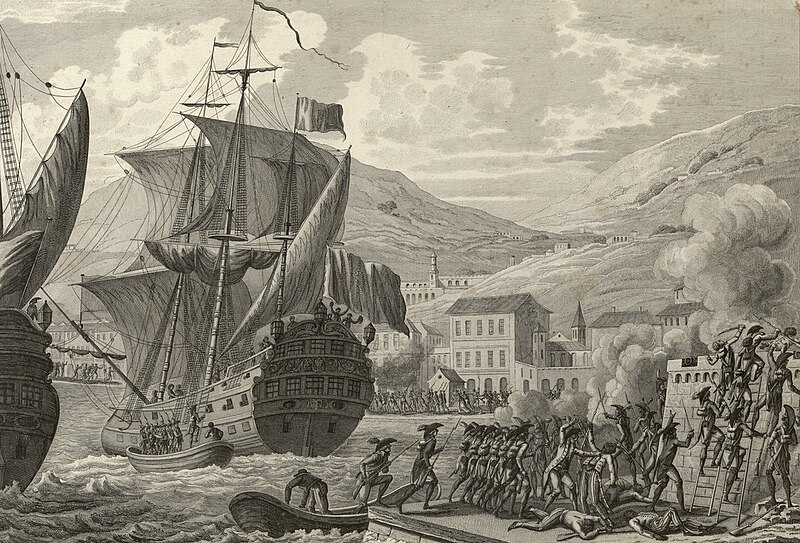

A typical scene of the early stages of the Haitian Revolution: rebel slaves massacring their masters' subordinates and families.

That night, under the leadership of Dutty Boukman and other prominent figures among them, tens of thousands of slaves rose up in revolt all over the northern half of Saint-Domingue, catching their oppressors, already busy fighting each other, completely by surprise. Armed with machetes and other agricultural tools, the rebels, whose numbers multiplied in a matter of days, destroyed hundreds of plantations and killed at least 4.000 people, most of whom were civilians, within two months. Despite a brutal reaction by the whites and colonial authorities, who committed their own massacres and eventually killed Boukman on November 7 1791, they were unable to stop the rebellion from spreading to the south. The Haitian Revolution had begun.

To say that the situation in Saint-Domingue became chaotic from that point onward would be the mother of all understatements: French rule over the colony was reduced to some scattered strongholds here and there, while the whites, free people of color and rebel slaves fought brutal battles against one another. It was a scenario that became even more hectic after 1792, since Spain and Great Britain got involved following the outbreak of the War of the First Coalition. Both countries desired Saint- Domingue's riches for themselves, and it didn't take long for them to find allies among the combatants: the British secured the grand blancs' allegiance by promising to restore slavery, while the Spanish promised to recognize the rebellious slaves' freedom as long as they fought for them. France, desperately clinging to what was once its crown jewel by its fingertips, had the support of the free people of color.

It was a free for all, and the war in Hispaniola devolved into a stalemate - the fighting was just too brutal, and repeated outbreaks of yellow fever wreaked havoc among the combatants, especially the British. Alliances were broken almost as soon as they were made, the situation in the island dependent on battles fought thousands of kilometers away in distant, distant Europe. It was a fickle, treacherous state of affairs, albeit one which could bring great benefits for someone cunning and lucky enough to exploit it.

That someone was Toussaint Louverture.

Toussaint Louverture, the public face of the Haitian Revolution.

Despite being born into slavery on May 20 1743, one could argue Toussaint had been a lucky man from the get go: he, along with his siblings, was trained to be a domestic servant in his master's household, which spared him from the grueling, deadly work in the sugarcane fields. He was also clearly given a reasonable degree of education during his youth, as shown by surviving letters of his which reference philosophers like Epictetus and Machiavelli, even if documentary evidence shows he apparently didn't know how to write until somewhat late in his life (1). Manumitted sometime during the 1770s (when he was in his thirties), Toussaint became an overseer in the plantation he was born before becoming a slaveowner himself, owning a small coffee plantation. He was, at least as far as the propaganda goes, almost uniquely adapted to take advantage of the environment created by the revolution: his past as a slave (and lack of European ancestry) tilted him towards the rebel cause, while his knowledge of colonial high society meant he was better suited to negotiate with whites and wealthy people of color than most of his colleagues.

As with other major leaders of the slave rebellion, Toussaint spent the early years of the war as an ally of Spain, which, from its colony of Santo Domingo, supplied weapons, uniforms and ammunition to the men under his command. They became a force to be reckoned with, disciplined enough to meet their enemies in open battle yet still capable of retreating into the countryside to wage a guerrilla war if necessary. But the Spanish alliance wasn't perfect, not only because said country was losing the war in Europe, but also because it meant the rebels were technically allied with Great Britain, whose intention to restore slavery was, naturally, anathema to them. Sensing the direction the winds were blowing, and with France becoming increasingly favorable towards abolitionism, Toussaint, who was until then a devoted royalist, became a loyal revolutionary in early 1794.

With the British languishing on the shores, dying in droves from yellow fever, and with the help of Toussaint and lieutenants, many of whom were brave and capable generals in their own right, the French had no trouble reestablishing their control over Saint-Domingue, kicking the Spanish out of their colony in a matter of weeks. Their position became even stronger, at least on paper, following the Peace of Basel, signed in 1795, in which Spain agreed to hand its part of Hispaniola to the French in the future, who eventually uniting the island under their rule. The real winner, however, was Toussaint: he outfoxed or eliminated several potential rivals through his skilled politicking and double dealing, and was now not only a respected general, but also a very wealthy man, with many properties all over Saint-Domingue. He was poised to take the governorship, and that was exactly what he did on August 1797, when he forced Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, the post's occupant at the time, to return to France (2). It was a power grab that raised some eyebrows in Paris, but the Directory had bigger issues to deal with closer to home.

Though he reaffirmed his loyalty to France, Louverture pursued an independent foreign policy as governor, securing an agreement with Thomas Maitland, commander of the British troops in Saint-Domingue, stipulating their withdrawal in exchange for an amnesty for those who collaborated with them. With that immediate threat dealt with, he dispatched Joseph Bunel, a grand blanc and former planter, to the United States, to help secure a trade agreement between said country and Saint-Domingue. Bunel would later meet with president John Adams, and "Toussaint's Clause", as the proposal became known, was approved by Congress in early 1799. American ships were allowed to land in Dominican ports and trade with the locals, even as the US and France waged an undeclared war against one another.

Maitland meeting with Louverture.

On the domestic front, Louverture sought to rebuild the Dominican economy, ruined by successive years of war. With the colony's treasury wholly dependent on the export of cash crops, the governor forced the former enslaved back into the plantations they so hated, instituting a system of forced labor whose productivity was secured through the use of the military. Louverture's popularity soured, the benefits given to the former enslaved (such as salaries and the abolition of whipping) not enough to keep them from launching small rebellions every now and then. Still, things began to improve on a macroeconomic level, and Toussaint's good relations with Britain and the US gave him two critical allies in the struggle that was to come, for while the Europeans were pulling back from Saint-Domingue, the governor still had one last adversary to deal with.

His name was André Rigaud, a free man of color who became Vincent Ogé's unofficial successor as champion of his class' interests. While Toussaint held power in the north, the region in which he was born, Rigaud ruled the south, restoring the region's plantations just like his northern counterpart did, though lacking his foreign connections. It was an unsustainable state of affairs, one which was worsened by a French representative who sowed tensions in an attempt to curb Louverture's power, and the two men and their supporters finally came to blows in June 1799. Their brief but brutal conflict became known as the War of Knives, and, after some initial setbacks, Toussaint scored a complete victory over his rival. This came in no small part thanks to the help of the United States Navy, which blockaded ports controlled by Rigaud's troops and provided fire support to Toussaint's forces whenever possible.

Now at the height of his power, Toussaint ordered an invasion of Santo Domingo, which was still under Spanish control despite the terms established by the Peace of Basel. His soldiers marched into the colony virtually unopposed, turning their leader, a man who was born a slave, into the undisputed dictator of all of Hispaniola. He had, however, crossed one line too many: he had effectively become the ruler of an independent state, a state another military dictator, a certain Napoleon Bonaparte, sought to put back under French control. A new constitution was elaborated in Paris, one that, by stipulating that French colonies would be subjected to "special laws", opened the way for a potential restoration of slavery in Saint-Domingue. Toussaint responded to this by summoning his own constituent assembly (made up primarily of white planters) in March 1801, and the constitution they created came into force in July 1801. It outlawed all forms of racial discrimination, stipulated that slavery would never return, and, most importantly, declared Toussaint governor for life, with near absolute authority and the right to appoint his successor.

It was, for all intents and purposes, a declaration of independence.

French troops landing in Cap-Français.

France's response came in February 1802, when 30.000 men led by Charles Leclerc, Napoleon's brother-in-law, landed and captured several ports all over Hispaniola without resistance. Toussaint withdrew to the interior, intending to wage a guerrilla war until yellow fever weakened the invaders enough for his troops to strike back. It was a strategy was hampered by dissent and bad communications: while some generals complied with his commands to wage a scorched earth policy, in order to deny the French as many supplies as possible, others either didn't receive or refused to obey them. Leclerc took advantage of this lack of unity by employing a conciliatory approach, promising not to reinstate slavery, while the rebel leaders would maintain their ranks in the French military if they surrendered peacefully. He had no intention of honoring the latter promise, not least because he was under secret orders from Napoleon to deport all black officers from Saint-Domingue the moment they entered his custody.

Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe, two of Louverture's most respected lieutenants, accepted these terms, prompting their superior to do the same on May 6 1802. Instead of being treated like a retired general, however, he was put under house arrest in one of his estates, while Leclerc attempted to assert his authority as governor and made the necessary preparations to deport him. Isolated pockets of resistance continued to fight on in the countryside, and the same diseases that forced the British to withdraw four years prior began to bite. To make matters worse for the French, news arrived stating that slavery had been reimposed in Guadeloupe, much to the horror of the ex-slaves who, besides forming the backbone of the rebel army, made up the overwhelming majority of the Dominican population.

Finally, as if that weren't enough, Toussaint was able to escape from the house arrest he was under on May 30, days before his deportation to France was scheduled to take place (3). Christophe and Dessalines defected to his side not long after, and Leclerc's control over Saint-Domingue was restricted to the coast in a matter of months. With the failure of the diplomatic solution, Leclerc concluded the only way France could reestablish control over its rebellious colony was through the complete genocide of its black inhabitants, a goal he intended to accomplish by killing every person over the age of twelve. His successor as commander of the French army, the Vicomte de Rochambeau, took an even more brutal approach, importing thousands of attack dogs from Jamaica and turning his ships' cargo holds into rudimentary gas chambers. All these atrocities did was convince the former slaves and free people of color to leave their old rivalries aside (for the time being, at least) and unite their forces.

Massacres followed. Whenever the French executed black prisoners, usually by hanging or drowning them, the rebels responded in kind, in one occasion executing the same number of French soldiers under their custody shortly after one such massacre, then putting their severed heads on wooden spikes in plain view of their enemies. This brutal tit-for-tat continued for months on end, and all the while the French position continued to decay, weakened by successive defeats on the battlefield and the inexorable march of yellow fever on their ranks. Things only got worse for the invaders in 1803, when France and Great Britain resumed hostilities, and a Royal Navy squadron was dispatched to blockade the last French holdouts in Saint-Domingue. Surrounded by enemies, beset by disease and cut off from reinforcements, Rochambeau finally capitulated, and his exhausted troops left Cap-Français on December 1 1803.

Toussaint's soldiers entered the city the next day, and Saint-Domingue was no more. A new country was born, and its founders named it Haiti after the indigenous name for the island it was located. For the last few whites who, despite everything, stayed behind in places like Le Cap and Port-au-Prince, the days that followed must've been nerve-wracking: the war had been long and rife with atrocities, and they were now at the mercy of a group they had looked down upon for centuries.

But, in spite of the rivers of blood that had already been spilled and the near apocalyptic predictions of many slaveholders and racists abroad, the massacre so many of them feared never came (4). Instead of unleashing his soldiers against the white population, Toussaint asked them to send representatives to form a new constituent assembly, so as to craft a constitution better suited to Haiti's current predicament. They were joined by representatives from the free people of color and the former enslaved, the latter of whom had a plurality of seats, and the assembly convened on February 7 1804. Toussaint opened discussions with a blistering attack on the French Revolution, arguing the republic it created was not only weak, but acted against its supposed ideals by trying to force the people who had more than earned their freedom back into bondage. Haiti, he proclaimed, needed a strong leader, one who could keep the nation united and safe from foreign threats.

It needed a king.

A pamphlet celebrating Haiti's new constitution, giving it a near divine aura.

With this speech, Toussaint's career came full circle: he started as a royalist who fought for Spain, became a republican on France's side, then returned to his roots after independence (5). Republicans like Alexandre Pétion and Jean-Pierre Boyer were horrified, and their accusations that Toussaint intended to become a hereditary monarch were undercut after he declared that not only was such a decision solely in the hands of the constituent assembly, but he would not present himself as a candidate. With his prestige and control of the military, whose presence was a constant whenever the assembly convened, Louverture inevitably got his way: the constitution, promulgated on June 12 1804, stipulated that Haiti would be a monarchy, governed by a king whose powers had almost no restrictions whatsoever, while the legislature would be composed of a National Assembly and a Senate. Once again, all forms of racial discrimination were outlawed.

True to his word, Toussaint stayed out of the royal election, and the constituent assembly, after a few days of deliberation, chose Henri Christophe, one of his top generals, to become the first king of Haiti. Following Henri's coronation in August 11 1804, Toussaint retired to his estate in Ennery, where he would spend the last years of his life. While his decision to let go of power is portrayed by contemporary and later propaganda as an act of magnanimity worthy of a modern Cincinnatus, it is more likely that Toussaint was just too exhausted to keep governing. He was already in his late forties by the time the Haitian Revolution began, and the stress of the subsequent years of war ruined his health. Case in point, Louverture died in October 5 1807, just three years after his retirement. He was sixty-four years old (6).

While the worst of the war had passed, things were far from smooth sailing for the newly crowned Henri I. Leclerc's invasion had further devastated the plantations that formed the bedrock of Haiti's economy, and it would take years of rebuilding to get them back up to speed. His election as king wasn't without issue either, since there was a sizable faction in the military which favored Jean-Jacques Dessalines, another prominent general in the Haitian army, and rumors of a coup began to circulate in the streets of Cap-Haitien (formerly Cap-Français) almost as soon as the festivities associated with his coronation died down. Lastly, the republicans, who had many supporters among mixed race Haitians, were opposed to his rule by default.

Henri I of Haiti.

Fortunately, Henri could count on support from Great Britain, which saw him as an useful ally against France due to the Napoleonic Wars, and the United States, whose ties with Haiti only strengthened following John Adams' reelection in 1800 (7). He also had a big, juicy target he could turn his restless army on: the formerly Spanish colony of Santo Domingo, still under French occupation despite the catastrophe that engulfed their forces on the western side of Hispaniola. Their position there was comparable to a house of cards, however: their troops were small in number, with no hope of receiving reinforcements from France, and the local Spanish colonists were already contemplating rebellion.

Thus, when king Henri dispatched an army of 25.000 men under general Jean-Baptiste Riché to invade Santo Domingo in February 1805, his advance was virtually unopposed. The Spaniards were brought to their side through promises of fair treatment and economic development (Santo Domingo had long been neglected, even before the French occupation), promises validated by the Haitians' treatment of their own white population back home. More than a few found the idea of being ruled by a black man baffling at best, but even then he was a preferable alternative to the French. It wasn't until the Haitians reached the gates of Santo Domingo city itself that they at last met some sort of resistance, but the odds were so overwhelmingly in their favor the French surrendered after a short siege (8).

By March 1805 the island of Hispaniola was reunified, this time under Haitian rule, and the long, grueling task of securing its independence could finally begin. It was a journey whose steps would be watched by politicians and intellectuals from all around the world, all of whom with very strong opinions on the subject. For some, Haiti's name would be equated to hope and freedom, while others were terrified by its mere existence.

------------------

Notes:

(1) This is all OTL, at least according to his wikipedia article.

(2) Funnily enough, Toussaint accused Sonthonax of wanting to massacre Saint-Domingue's white population. A bit ironic, considering what Dessalines would later do.

(3) This is the big POD of this update. IOTL Toussaint was taken to France and eventually died there, while the leadership of the rebellion fell in the hands of Dessalines.

(4) A sharp departure from OTL, to say the least.

(5) Toussaint switched sides whenever it suited him IOTL, though he stayed loyal to his abolitionist principles once he adhered to them. Also, a monarchy does have a plus compared to a presidency for life, in that there's a clear line of succession.

(6) Toussaint died in 1803 IOTL. I figured it'd be plausible for him to live a few more years if he isn't left to rot in a French prison.

(7) Long story short, news of the end of the Quasi-War reach the US in enough time to swing the 1800 election in Adams' favor. I'll hopefully write an update focused on the consequences of Adams' reelection in the future, but there's a whole other bunch of stuff I want to handle already.

(8) Dessalines and Christophe tried to conquer Santo Domingo in 1805 IOTL, but failed. Their forces massacred almost a thousand civilians during their retreat back to Haiti.

Last edited:

Great chapter, hopefully Haiti will have a better future than OTL and with France much more preoccupied in Europe means they hopefully won't be able to impose the same destructive debt of OTL.

Great chapter, hopefully Haiti will have a better future than OTL and with France much more preoccupied in Europe means they hopefully won't be able to impose the same destructive debt of OTL.

I'm not quite sure, remember war in Europe will come to an end leaving France in far better shape than its otl counterpart and post Napoleonic Europe will still have similar political landscape focused on balance of power.

Not to mention Napoleon ruling France means a far more stable and legitimate government. Honestly it's quite likely that imposing that debt is the least French can do to Haiti.

It seems apparent WHY the American South will see a nation rule run by a Black Monarch as an existential threat to their power. Same could probably apply to European nations as well.By March 1805 the island of Hispaniola was reunified, this time under Haitian rule, and the long, grueling task of securing its independence could finally begin. It was a journey whose steps would be watched by politicians and intellectuals from all around the world, all of whom with very strong opinions on the subject. For some, Haiti's name would be equated to hope and freedom, while others were terrified by its mere existence.

A monarchy in Haiti is the best plausible outcome in these troubled times...

No matter how secular or ideal the revolution was, racism never seemed to lose fuel in any part European political spectrum until much later. Good for him to call out the hypocrisy.Toussaint opened discussions with a blistering attack on the French Revolution, arguing the republic it created was not only weak, but acted against its supposed ideals by trying to force the people who had more than earned their freedom back into bondage.

Part 18: An Eagle Reborn

------------------

Part 18: An Eagle Reborn

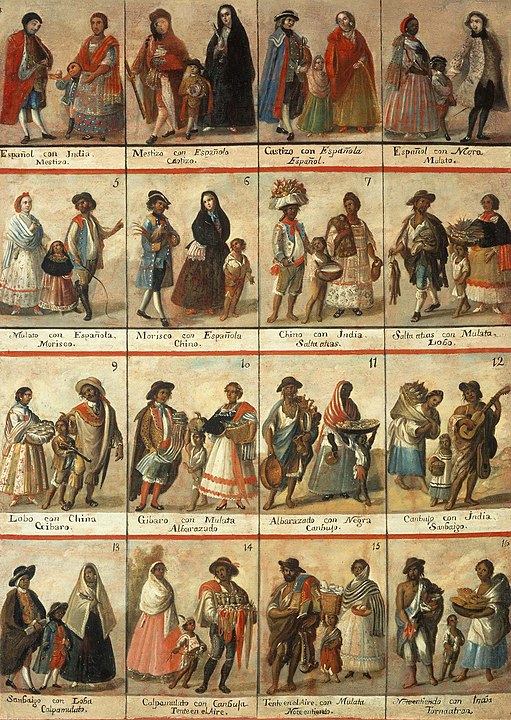

As with almost every European colony in the early 19th century, the Viceroyalty of New Spain could be compared to a cauldron, full of social and economic tensions simmering just beneath the surface. Built on the foundations laid by the Aztec Empire and various other native civilizations conquered by the Spanish, New Spain was one of Madrid's crown jewels in the Americas, together with the Viceroyalty of Peru far to the south. Its wealth and splendor, sustained first and foremost by silver mining, then farming and trade with the Philippines (another Spanish colony), made the colony the object of much dispute not just between Spain and other great powers, but its inhabitants as well. As with other Spanish colonies, New Spain's society was dominated by the peninsulares, Spaniards born in Europe who occupied most of the important administrative posts. Just below them were the criollos, local-born whites with varying degrees of native ancestry who, despite being quite wealthy in some cases, had their interests sidelined in favor of the peninuslares' more often than not.

In a society where ancestry and skin color were just as important as material wealth to determine one's social status, the further down one went through New Spain's hierarchy, the more likely it would be for said individual to possess more and more indigenous blood flowing in their veins. The middle class, exceedingly small in a society as unequal as this, was made up of poorer whites and mestizos (mixed race people) who served in a variety of professions, from doctors to lawyers to clerks and shopkeepers. Finally, the bottom was occupied by large masses of mestizo and native farmers, the lucky ones among them living and working in communal farms (the ejidos) while those who weren't worked in haciendas (large estates) owned by the criollos and peninsulares.

Part 18: An Eagle Reborn

As with almost every European colony in the early 19th century, the Viceroyalty of New Spain could be compared to a cauldron, full of social and economic tensions simmering just beneath the surface. Built on the foundations laid by the Aztec Empire and various other native civilizations conquered by the Spanish, New Spain was one of Madrid's crown jewels in the Americas, together with the Viceroyalty of Peru far to the south. Its wealth and splendor, sustained first and foremost by silver mining, then farming and trade with the Philippines (another Spanish colony), made the colony the object of much dispute not just between Spain and other great powers, but its inhabitants as well. As with other Spanish colonies, New Spain's society was dominated by the peninsulares, Spaniards born in Europe who occupied most of the important administrative posts. Just below them were the criollos, local-born whites with varying degrees of native ancestry who, despite being quite wealthy in some cases, had their interests sidelined in favor of the peninuslares' more often than not.

In a society where ancestry and skin color were just as important as material wealth to determine one's social status, the further down one went through New Spain's hierarchy, the more likely it would be for said individual to possess more and more indigenous blood flowing in their veins. The middle class, exceedingly small in a society as unequal as this, was made up of poorer whites and mestizos (mixed race people) who served in a variety of professions, from doctors to lawyers to clerks and shopkeepers. Finally, the bottom was occupied by large masses of mestizo and native farmers, the lucky ones among them living and working in communal farms (the ejidos) while those who weren't worked in haciendas (large estates) owned by the criollos and peninsulares.

A painting from the mid 18th century depicting various colonial families, and the names given to each racial category.

While New Spain was fraught with tensions among its inhabitants, especially between the criollos and the peninsulares, from the get go, the Spanish Crown's actions over the course of the 18th century did much to worsen the situation. The House of Bourbon, which came to power in Madrid after almost two centuries of Habsburg rule, sought to reassert Spain's supremacy over its myriad colonies, as well as crack down on corruption and smuggling (which, in that age, consisted of commerce with any country other than Spain). The Bourbon Reforms, as they became known, crippled the criollos' power while strengthening that of the peninsulares, with the latter being given practically all of the new administrative posts which were created.

By the early 19th century, the situation had become ever more difficult to tolerate. Spain's involvement in the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars after that, led to a succession of tax hikes, spurred by need to fund the Spanish war effort in Europe and protect New Spain's lengthy coast from possible British attacks. Although the incumbent viceroy, José de Iturrigaray, was reasonably popular thanks to the various internal improvements under his watch, as well as his authorization of bullfights on colonial soil, he was powerless (or perhaps not interested, given subsequent events) to stop the circulation of increasingly radical ideas among the criollos. With the United States and later Haiti showing it was possible to set up an independent state in the New World, the only thing left to set off a similar chain of events in New Spain was a spark.

And the French invasion of Spain provided exactly that.

News of the Abdications of Bayonne, and the utter mayhem that followed, reached the Americas in a matter of months, and the already fragile political situation gave way to an outright crisis. With the mother country desperately fighting for its independence, the colonies were left to their own devices, unsure of who to answer to now that the rightful king, Ferdinand VII, was under house arrest in a French château. The criollos in the colonies, eager to take advantage of the power vacuum, called for the creation of local juntas, not unlike the ones set up in Spain itself, to administrate the colonies until the Bourbons were restored, while the peninsulares, fearful of any change which could undermine their supremacy, were intransigent defenders of the status quo.

New Spain was no exception to this phenomenon. Word of the events in Europe reached the colony's shores in mid July 1808, and the local criollos wasted no time in making their voices heard. On July 19 1808, viceroy Iturrigaray received from the cabildo (city council) of Mexico City, dominated by criollo representatives, a proposal to establish a junta, whose purpose would be to govern the colony in king Ferdinand VII's stead until his eventual restoration to the Spanish throne. He acquiesced despite the objections made by the Royal Audiencia of Mexico, New Spain's highest court and a stronghold of the peninsulares, which argued that anything other than complete loyalty to the directives laid out by the junta of Seville (the Supreme Central Junta hadn't been established yet) was an act of rebellion against the crown. Their position was backed by merchants whose fortunes depended on New Spain's economic subjugation to its colonial overlord, the Inquisition, and the archbishop of Mexico, Francisco Javier de Lizana y Beaumont.

The junta, presided by the viceroy and made up of 82 representatives who belonged to the military, clergy and civil society in general, first convened on August 9. Two criollo members of the Mexico City cabildo, Francisco Primo de Verdad y Ramos and Juan Francisco Azcárate y Lezama, argued that, with the king unable to exercise his power, such responsibility ought to be given to the people of New Spain, who would be represented by the various municipal councils which already existed, along with other institutions (1). Naturally, the peninsulares' delegates balked at this proposal, as did many more moderate and conservative criollos - such a move could easily snowball into outright independence from Spain, which was off the table for everyone except the most radical among their class.

Juan Francisco Azcárate y Lezama, one of the leaders of the criollo party.

Ultimately, the junta's first meeting accomplished nothing. As August 1808 wore on, the only things the viceregal government could do without sparking controversy were symbolic acts such a public oath of loyalty to Ferdinand VII, which was made on August 13. The situation became even more delicate after the arrival of two commissioners sent by Seville to assess the situation in New Spain, and they wasted no time before scheming with their fellow Europeans against Iturrigaray and the criollos, who were increasingly seen by them as one and the same. To make matters worse for the viceroy, he couldn't count on the loyalty of all of New Spain's intendancies (provinces), either: while México and Veracruz were solidly behind him, the governors of Puebla and Guanajuato, as well as the audiencia of Guadalajara, repudiated the authority of the junta in Mexico City and remained loyal to Spain alone, even if the country in question lacked a centralized government at the moment.

Further meetings of the junta did nothing except increase the animosity between criollos and peninsulares, with the Audiencia, backed by the Sevillan commissioners, outright accusing Iturrigaray of incompetence on one occasion. The viceroy responded by revoking New Spain's official recognition of the Seville junta as its colonial overlord, stating instead that all Spanish juntas were equal in authority. By September, it was clear it was only a matter of time before open fighting broke out between both sides' partisans. With no compromise in sight, the ideas of Melchor de Talamantes, a Peruvian-born friar who called for the election of a congress to decide New Spain's destiny, rather than a mere provisional junta, became increasingly appealing to the criollo party.

Finally, the peninsulares decided enough was enough - if the viceroy wasn't willing to repress their adversaries' clearly seditious activities, they'd replace him with someone who was. With the acquiescence of archbishop Lizana and the Sevillans, the peninsulares of Mexico City, led by a prominent landowner and trader named Gabriel de Yermo, began to gather weapons and men to depose Iturrigaray and, after that, begin an all out crackdown against the criollo party. The plotters intended to put their plan in motion on the night of September 15 to 16, when they would gather the forces at their disposal - some 300 men, to be led by Yermo in person - storm the viceregal palace and arrest Iturrigaray before his allies could react.

Unfortunately for the conspirators, their plot wasn't as secret as they thought. When Yermo and his supporters, believing to be safe under the cover of darkness, assembled and prepared to march towards the viceregal palace, they were met and fired upon by troops loyal to the government. They never stood a chance: caught by surprise, many, including Yermo himself, were killed before they could use their weapons, and several others surrendered to avoid the same fate. As the sun rose over the streets of Mexico City on September 16, viceroy Iturrigaray had full control of the situation, and, after months of relative timidity, finally acted on a decisive manner (2).

Gabriel de Yermo, whose failed coup assured Mexican independence.

Several prominent peninsulares, including archbishop Lizana and members of the Audiencia, were arrested, and furious mobs ransacked properties owned by them. Word of the events in the capital spread like wildfire, and soon similar bouts of unrest broke out in other major cities, street battles breaking out as local criollos and mestizos saw a chance to finally act on their old grudges against the Europeans. They, meanwhile, took up arms to defend themselves, and local authorities were at a complete loss on what to do and who to obey - bad roads meant information took a long time to spread, and when it did reach its destination it was often either obsolete or distorted by hearsay. Juntas popped up on every corner on a nigh spontaneous manner, formed by peninsulares and criollos alike, all fighting for supremacy over their respective regions (3).

Surprisingly perhaps, this scenario of utter anarchy was short-lived, especially when compared to the long, horrific wars which took place in other Spanish colonies. The peninsulares' strongholds were scattered and, most importantly, leaderless, while the criollos could count on support from the highest authority in the land. After dispatching a flurry of messages to various cabildos known to be loyal to him (such as the one which governed the critical port of Veracruz), and purging the viceregal army of royalist elements, viceroy Iturrigaray ordered a series of military campaigns against peninsular holdouts. Hopelessly outnumbered and assailed by enemies within and without, most surrendered without a fight - the most serious resistance was offered by New Galicia, an autonomous state centered in Guadalajara, but even it was forced to give up in the face of overwhelming odds.

Thus, the situation in New Spain was (mostly) resolved by January 1809. No longer hiding his affinity for the criollo party's ideas, José de Iturrigaray, still acting in the name of the Spanish king but now an independent ruler in all but name, issued a decree calling for the election of a congress, as first proposed by Melchor de Talamantes months before. Made up of 107 deputies elected from all over New Spain, this assembly, which became known as the Congress of Anahuac, first convened in Mexico City on March 7 1809 (4). However, it didn't take long for the criollos' joy at finally attaining the power they sought for so long to be replaced by a fierce debate on what to do with that power. With the unifying force provided by the threat of the peninsulares gone for the time being, the Congress' sessions became increasingly heated, with two factions forming: the federalists, who called for a decentralized state and were open to a republic, and the centralists, who, as their name suggested, supported a strong central government and were almost unanimously supportive of a monarchy.

Before the gridlock could become too severe, however, the government received two news which served as a well timed wake up call.

First was that Spain had, at long last, established a coherent government (the Supreme Central Junta) capable of communicating with its colonies, even if it couldn't send troops to the Americas yet as a because of the ongoing war with the French. This government, centered in Seville after the fall of Madrid, not only demanded that Iturrigaray relinquish his post, but had already designated a substitute for him: Francisco Javier Venegas, a general who took part in the Battle of Bailén and other, less successful clashes with the Grande Armée. Needless to say, Venegas was arrested the moment he set foot in Veracruz and sent back to Cuba on March 29 1809, an act which served as a de facto declaration of independence, even if the official one would come only months later (5).

The other news came from the Captaincy General of Guatemala, nominally a part of New Spain, but one so far away from Mexico City's reach it was effectively a different colony altogether. Word of the events further north reached the captaincy's inhabitants in a matter of months, and, despite governor Antonio González Mollinedo y Saravía's best attempts to keep a tight lid on things, local criollos soon began to plot their own rebellions in their respective intendancies (6). News of these developments, combined with the unofficial declaration of war on Spain that was made through Venegas' deportation, convinced many movers and shakers in Mexico City that Guatemala had to be conquered, not just for the sake of military glory, but to deny the Spanish a potential point through which they could launch an invasion of their new (and still unnamed) state's southern territories.

With all these factors in mind, Iturrigaray didn't need much convincing to call up an army to bring Guatemala under the fold. This army, made up of 24.000 men once fully mustered, was assembled in the city of Tehuantepec, right next to the border of the territory it was meant to invade, and was put under the command of Agustín de Iturbide, an ambitious criollo who benefited from the purge of Spanish officers in the viceregal army (7). After months of planning, further correspondence with their fifth column and gathering supplies, the not-yet-Mexican army entered Guatemala on May 27 1809, scattering all Spanish forces before them. A huge uprising broke out in the intendancy of San Salvador once the conspirators there got word of the invasion, and they swept over most of the province in a matter of days. A similar revolt took place in Nicaragua, its followers taking the cities of León and Granada in quick succession (8).

Outmatched in every way and attacked from multiple sides, Saravía had no choice but to surrender once Iturbide's troops came within sight Guatemala City on June 19 1809. In a little over than a year, Spain had gone from master of Central and (much of) North America to losing all of its continental territories north of Panama, save for Florida. Needless to say, it wouldn't take long for the consequences of such momentous developments to be felt further south.

A painting commemorating the uprising in San Salvador.

José Matías Delgado, one of its main leaders, is in the center.

The annexation of Central America had immediate, longstanding effects on Mexican politics. The provinces that once belonged to the Captaincy General of Guatemala were allowed to send representatives to the Congress of Anahuac, and since most of these had goals which aligned with planks defended by the federalists (as they did not want to simply exchange one overlord for another), the balance of power in the Congress shifted away from the centralists decisively. This did not mean, however, that they would get their most ambitious goals satisfied: several of them were quite moderate, more willing to negotiate with their nominal adversaries than with their more radical 'colleagues'.

At long last, after months of back and forth arguing and voting on proposal after proposal, the Congress of Anahuac finished, on October 7 1809, the document it had been elected to create. Known as the Act of Independence of the Mexican Empire, it declared, among other articles, that:

- Mexico is an independent nation, free from the rule of Spain and any other government not chosen by its own people;

- Its territory is divided in provinces, which can be further divided if deemed necessary;

- Each province is free to handle its own affairs, though its power is strictly restricted to its own borders;

- Its government is a constitutional monarchy, headed by an emperor;

- With the absence of a current reigning dynasty, the first emperor will be chosen by Congress;

- Governing power is to be divided between three branches: the executive, legislative and judiciary;

- The executive power is to be exercised by the emperor and ministers of state, the legislative by the National Assembly (made up of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate), and the judiciary by the Supreme Court of Justice;

- The emperor has the authority to appoint and demote ministers, as well as veto laws passed by the National Assembly;

- The National Assembly is to be elected every four years, though it can be dissolved earlier through a vote of no confidence;

- The right to vote and be elected is restricted to men 25 years of age or older, and such men also need to meet a minimum income;

- The state religion is the Roman Catholic Church, but other faiths can be practiced in private.

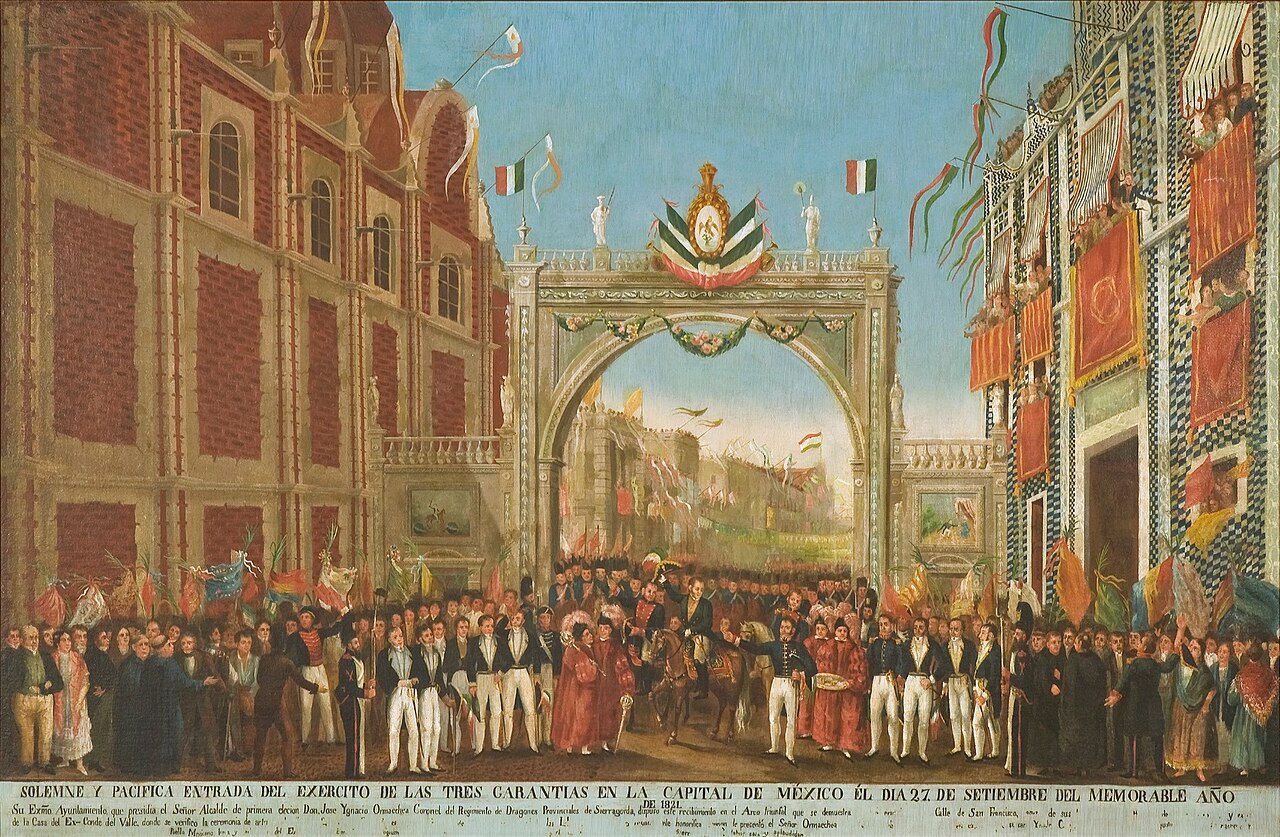

In the end, both federalists and centralists achieved their most important goals. The former got the provincial autonomy they so desired, as well as a clear separation of powers, while the latter got their monarchy (which, while not an absolutist one, was still quite powerful) and Catholicism's status as Mexico's official religion, a state of affairs which would secure the Church's properties for decades to come, to the ire of many liberals. When time came for the Congress of Anahuac to decide who would be their new country's first emperor, a few days after the approval of the Act of Independence, only one name was even worth considering: José de Iturrigaray, the viceroy who spearheaded the process that ended Mexico's status as a Spanish colony. Crowned José I on December 17 1809, he was the first monarch to be crowned in the American continent, and, at sixty-seven years of age, also the oldest. His reign was fated to be a short one, and no one knew if his eldest son, also named José, would be able to fill his shoes when the time came (9).

Last but not least, the Congress voted on what flag for their country to use. Several designs were presented, but, in the end, the flag that won was one which combined elements which represented both the future and the past: a tricolor, not unlike the French one, and an eagle perched atop a cactus, a symbol used by the Aztec Empire of old. It also represented the circumstances in which the Mexican Empire was born, marching towards the future but without forgetting its past.

Last but not least, the Congress voted on what flag for their country to use. Several designs were presented, but, in the end, the flag that won was one which combined elements which represented both the future and the past: a tricolor, not unlike the French one, and an eagle perched atop a cactus, a symbol used by the Aztec Empire of old. It also represented the circumstances in which the Mexican Empire was born, marching towards the future but without forgetting its past.

Festivities associated with the coronation of José de Iturrigaray as emperor of Mexico.

------------------

Notes:

(1) This was the main argument used by supporters of independence throughout Spanish America: with the mother country unable to govern its colonies, said colonies had the right to govern themselves.

(2) This is the big change, since the coup succeeded IOTL. Iturrigaray's substitute as viceroy was Pedro de Garibay, an elderly field marshal who was nothing more than a puppet for the Audiencia. A huge crackdown against prominent criollos ensued, with both Primo de Verdad and Talamantes dying in prison.

(3) Since they don't control the viceregal government like IOTL, the peninsulares have to fend for themselves.

(4) A congress with the same name existed IOTL.

(5) Venegas was viceroy when the Mexican War of Independence began IOTL.

(6) A large revolt broke out against Spanish rule in modern El Salvador in 1811, but it was repressed IOTL.

(7) Iturbide rose rapidly through the royalist ranks IOTL, so I figured it'd be plausible for him to lead an army.

(8) As with the revolt in El Salvador, this uprising was quickly suppressed by the Spanish IOTL.

(9) Special thanks to @jycee for finding out about Iturrigaray's family: https://gw.geneanet.org/sanchiz?lang=en&n=iturrigaray+arostegui&oc=0&p=jose

Last edited:

Phew! I'm honestly surprised this update was shorter than the Haitian one, it felt way longer when I was writing it.

Next one will deal with Peru, and probably Argentina at the same time since their independences were closely linked IOTL.

Next one will deal with Peru, and probably Argentina at the same time since their independences were closely linked IOTL.

Last edited:

It's more likely than you think! 😆Mexico? In MY Vinization TL?

Glad seeing this back! Hopefully this Mexico can be way more stable and prosperous as well as being able to stand against the US

Threadmarks

View all 19 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 12: One Final Effort Part 13: The Congress of Frankfurt Part 14: The Spectre of Revolution Part 15: Papers and Muskets Map: Europe after the Congress of Frankfurt Part 16: Carrots, Sticks and Daggers Part 17: A Beacon of Hope and Fear Part 18: An Eagle Reborn

Share: